1859

Florence Nightingale, widely regarded as the founder of modern nursing, made one of the earliest recorded observations of the emotional and psychological benefits of companion animals in healthcare settings.

While working in British military hospitals during the Crimean War and later writing about patient care, Nightingale noted that small pets—particularly dogs and birds—had a calming effect on psychiatric patients and the wounded. She observed that patients who were withdrawn, anxious, or severely ill often showed noticeable improvements in mood and responsiveness when allowed to interact with or care for an animal.

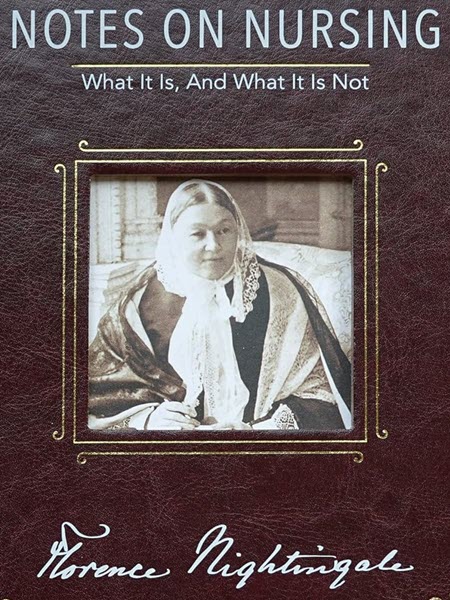

In her influential 1859 work, Notes on Nursing: What It Is and What It Is Not, Nightingale wrote:

“A small pet is often an excellent companion for the sick, for the long chronic cases especially.”

This simple statement reflected a profound insight: animals could provide comfort and companionship in ways that human caretakers sometimes could not. In the rigid, clinical settings of 19th-century hospitals, where mental illness was poorly understood and compassion was not always a given, the presence of an animal could ease suffering and bring a sense of normalcy.

While she didn’t use the modern language of “therapy” or “animal-assisted intervention,” Nightingale’s recognition of animals as a source of emotional support and healing paved the way for the more structured use of animals in mental and physical healthcare more than a century later.

Today, her observations are often cited as one of the earliest acknowledgments of the human–animal bond in medical care—a bond that would evolve into the formalized use of therapy dogs and other service animals in hospitals, rehabilitation centers, and beyond.